Abstract:

In the case of Fox Star Studios (Division of Star India Private Limited) v. Aparna Bhat & Ors.1, a Single Judge of Delhi High Court vide its order dated 11th January 2020, held that once a person has contributed to any cinematographic film in any manner, then as per the moral rights, he/ she has right to paternity. The Single Judge upheld an order dated 9-1-2020 of the Trial Court granting mandatory interim injunction in favour of the Respondent (Plaintiff in the original suit) and against the Petitioner / Appellant (Defendant in the suit) Further, the Single Judge applied the maxim of promissory estoppel in favour of the Respondent and against the Petitioner/Appellant to hold that a valid expectation had been created in the Plaintiff’s favour of having her work in the film recognized in the credits sequence. The Court thus held that the Plaintiff’s role in contributing to the film should be well recognized and acknowledged. Furthermore, the Court observed that there was no monetary benefit, or any other kind taken by the Plaintiff in lieu of her services and deserved the right to acknowledgement.

Facts of the case:

The present suit was in relation to a cinematographic film ‘CHHAPAAK’ which was released on 10th January 2020. The Respondent claimed that her contribution in the film was substantial, clearly recognized by the Petitioner via correspondences, and was also supposed to be suitably acknowledged in the film by Petitioner. The Respondent is a practicing lawyer and had represented the acid attack survivor Ms. Laxmi Agarwal, on who’s life the film ‘CHHAPAAK’ was based. It was the Respondent’s case that on 7th January 2020, she came to know of the absence of her name in the credits sequence of the cinematographic film when she was invited at the premier of the movie. She contended that she had neither any indication, nor any communication made to her stating that her role would not be acknowledged or recognized in the opening credits as earlier represented. The e-mails and other correspondences between the parties were placed on record by the Respondent to show that she played a significant role by contributing to the film and which was even recognized by the Petitioner in said correspondences and accordingly, she had approached the Trial Court seeking interim relief in the form of an injunction against the nationwide release of the film to public audiences. The Trial Court vide said interim order dated 9-1-2020 granted an ex-parte ad-interim relief stating that “…it is necessary that her contribution be acknowledged by providing on the slide of actual footage and images, the line “Aparna Bhatt continues to fight cases of sexual and physical violence against women” during the screening of the film…”. The Petitioner challenged the order of the Trial Court by means of the instant petition in the Delhi High Court wherein the present order has been passed.

Contentions of the parties:

The primary contention of the Petitioner was that there was an error on the part of Trial Court to grant an ex-parte ad-interim injunction. The Petitioner submitted that an ex-parte ad-interim injunction can only be granted to restore the status quo and cannot be granted to create a fresh state of affairs, by relying upon the judgment of Dorab Cawasji Warden v. Coomi Sorab Warden and Others2.

Further, it was contended by the Petitioner that the Trial Court went beyond the relief sought by the Respondent/Plaintiff as she had only prayed for restraint on the release of the film. However, the Court went beyond the prayers of the Respondent by ordering a mandatory injunction for inclusion of credits in the film which had not been sought by the Plaintiff/ Respondent. Also, reliance was placed on Rule 36, Section IV, Chapter II, Part VI of the Bar Council of India Rules by the Petitioner which states that it is barred to promote or advertise a lawyer and hence, if the credit sought for by the Respondent (being a lawyer) was not permitted under law, the same cannot be granted by the Trial Court.

It was further argued by the Petitioner that, there is no legal ground or basis in the case of the Respondent as even from a prima facie view of the matter, there seems to be no violation of any legal right of the Respondent. The Petitioner submitted that neither there was any contract between the parties nor any understanding/ agreement that was entered between the parties that could acknowledge the role of Respondent.

The Respondent/Plaintiff on the other hand submitted that she has been rendering pro-bono services for the acid attack victims for past more than ten years, and back in 2016, when she was approached by the Petitioner, the Respondent had entrusted upon them all her inputs and provided enormous help in the making and direction of the film. Reliance was placed on the extracts of the script wherein the Respondent/Plaintiff had personally made corrections, thus, evidencing her contribution to the film. Also, various email correspondences and other communications exchanged between the parties were placed on record establishing the understanding that the Respondent/Plaintiff would be acknowledged in the film. It was further submitted by the Respondent that by applying the principle of promissory estoppel, the relief sought ought to be granted. Further, the Respondent relied on various judgments to establish that even at the interim stage, an order which is similar to a final relief can be passed, viz. Deoraj v. State of Maharashtra and Ors.3, Sajeev Pillai v. Venu Kunnapalli[ FAO No. 191/2019], Saregama India v. Balaji Motion Pictures Limited[ CS (COMM) 492/2019], Kirtibhai Raval v. Raghuram Jaisukhram6.

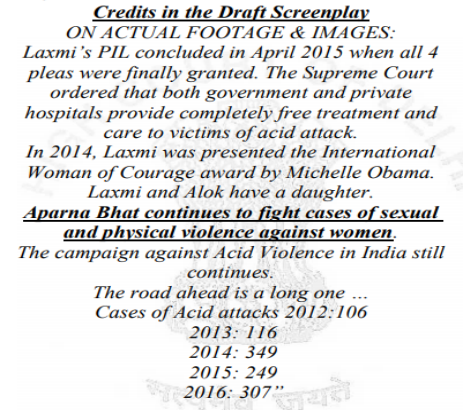

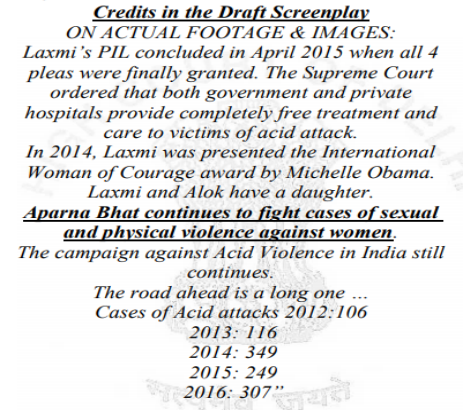

Furthermore, it was urged on behalf of the Respondent that other parties like Alok Dixit (NGO owner), who is also a contributor to the film, has been mentioned in the opening credits while her name has not been mentioned. Specifically, reliance was also placed by the Respondent on an e-mail dated 17th November 2018, in which a draft screenplay was shared by the Petitioner with the Respondent, wherein it was represented to the Respondent that her name would appear in the credits in the following manner:

The Single Judge observed that the above e-mail clearly shows that the Petitioner acknowledged the Respondent’s contribution in the making of the film. The Respondent stated that no such credit was given when the premier of the film was shown to the Respondent before the release of the film. The Respondent wrote a letter to the Petitioner stating that she expected her contribution to the film to be acknowledged but was not found in the final screenplay / credits, to which email the Petitioner replied as follows:

"Dear Aparna,

I am writing this as placeholder because as you rightly said, I do have too much going on. Between copyright cases to inclusion and exclusion complaints. (I guess just making this film wasn’t enough)

I will respond to your email once I’m relieved of my duties of releasing this film. Till then let be on record, that whenever I have detailed the real life characters w.r.t. to the film in any of my interviews, I have always mentioned you.

And perhaps acknowledged you and your contribution to Laxmi and the PIL in the film, more than Laxmi had ever done. You have said so yourself.

I will leave that with you. …”

The Respondent also relied on the judgment in the case of Monnet Ispat and Energy Limited v. Union of India and Others7 for seeking relief on the ground of promissory estoppel.

The Single Judge observed the e-mails exchanged between the parties and the draft screen play evidenced that the Petitioner clearly acknowledged the Respondent’s contribution, to which the Petitioner argued that there is no contract of service between the Plaintiff and the producers/director and no consideration was paid to the Respondent by the Petitioner.

The Ld. Single Judge observed the following:

- It is a settled legal position that the threshold to establish promissory estoppel is very high, and in order for any conduct to constitute promissory estoppel, there has to be a clear and unequivocal promise, which is intended to create a legal relationship, and that such promise would be binding;

- The correspondence between the parties shows that an expectation was created in the Respondent’s/Plaintiff’s mind that her inputs and contribution in the making of the film would be adequately acknowledged;

- There is no doubt that the non-acknowledgment of the contribution of the Respondent is contrary to what was represented to her since the inception of the making of the film;

- The effort, skill and labour of the Respondent cannot be undermined especially after a clear assurance, representation and promise was made to recognise her contribution;

- The consideration for the Respondent in rendering her services was not monetary but in the form of the recognition and she expected some form of acknowledgement of her role in the making of the film, since there no monetary consideration that was either demanded or given;

- It is also the well-settled position in law that in order for any person’s paternity rights in any work to be recognised, a written contract is not required (replying upon Neha Bhasin v Anand Raaj Anand & Anr.8. The right of paternity is an integral part of the moral rights of a person who makes any contribution; and

- The general rule is not to grant a mandatory injunction at the interim stage but the same can be granted to restore the status quo ante and to remedy a situation at once (replying upon Dorab Cawasji case9).

Decision by the High Court:

The Court ruled that the Respondent had not only provided help by contributing to the history of the criminal trial, the proceedings coming therefrom, and the public interest litigation filed at the Apex Court, but also gave documents, explained the nuances in detail of litigation processes and modified and corrected the script. Thereby, she has helped in the maintenance of the integrity and credibility of the film in respect of the legal journey gone through by the victim. The Court, besides relying upon the abovementioned observations and legal principles of paternity rights, promissory estoppel, and mandatory injunction, also relied upon the Supreme Court judgment in the case of Suresh Jindal v. Rizsoli Corriere Della Sera Prodzioni T.V. Spa and Others10 in order to reach its final conclusion. The Court stated that the Supreme Court in the Suresh Jindal case, when confronted with similar facts, held that the non-grant of relief would make the entire suit infructuous and that damages was not an adequate remedy, and also held that even ‘some part’ that the Plaintiff therein played in the film, deserves to be acknowledged. The Single Judge observed that while the recognition given by the Trial Court may be wide, the Respondent deserves to be acknowledged for her contribution to ‘some part’ in making of the film.

Accordingly, the Court restrained the Petitioners from releasing the film on any electronic medium without giving acknowledgement of the name of the Respondent in the opening credits in the following manner: “Inputs by Ms. Aparna Bhat, the lawyer who represented Laxmi Agarwal are acknowledged.”

Conclusion:

This case, thus, recognizes the right of a contributor to be credited and acknowledged for his/her contribution to the work. The contributor has paternity right under the moral rights allotted to a person under Section 57 of the Copyright Act, 1957 (part of moral rights). The Court in this case observed that if any person has contributed even ‘some part’ in making of a cinematographic film, then that person’s right cannot be prejudiced by not giving him/her any recognition or acknowledgement. In this particular case, there were admissions on the part of the Petitioner in the form of e-mails and other correspondences in relation to the work in making of the film which was contributed by the Respondent as evidence for her efforts as also communications which created expectations in the mind of the Respondent that her contributions shall be acknowledged. Thus, any person cannot be left unrecognized in case of contribution made to any artistic work in the absence of a contract to that effect. Further, an effective remedy can be provided in such cases by applying the principle of promissory estoppel and granting a mandatory injunction to the effect of acknowledging such contribution.

[The author is a Senior Associate in IPR practice in, Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan, New Delhi]

- CM (M) 15/2020

- (1990) 2 SCC 117

- (2004) 4 SCC 697

- FAO No. 191/2019

- CS (COMM) 492/2019

- Appeal From Order No. 262/2007

- (2012) 11 SCC 1

- (2006) 132 DLT 196

- Supra 2

- 1991 Supp (2) SCC 3