What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.

- William Shakespeare, Romeo & Juliet (Act II, Scene I)

Well, in the Indian GST regime, everything lies in the name. Last year, an Indian start-up approached the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) in India to determine the applicable rate of tax on “Whole Wheat Parotta and Malabar Parotta” - two popular Indian breads. The applicant contended that parotta is a type of roti and was classifiable under a category of bread covering “khakhra, plain chapatti or roti” attracting a rate of 5%. The AAR rejected the contention- it ruled that it was not roti (taxed at 5%) and that it was taxable at 18% as no specific entry covered the product and in its view roti and parotta are different. This is not a one-off case and in the area of food, the complications of classification are most pronounced.

In July 2017, India moved from an erstwhile indirect tax regime covering excise, Valued Added Tax (VAT), entry tax and other local indirect taxes to a unified Goods and Services Tax (GST). Giving credit where it is due, the GST regime had several positive impacts. It allowed credit to be seamless across borders, reduced the number of taxes to be complied with, boosted logistics and brought the entire country on a single platform. In a country like India with its complex federal structure, the implementation of GST has been note-worthy. But among the various compromises that needed to be made in order to roll-out GST, one of them was that India put in place one of the most complex classification structures for its goods and services. India adopted multiple slab-based GST rates (Nil,1,3,5,12,18 and 28) for various products with highest standard rate of 28% along with compensation cess. Most countries have either a single rate or two rates structure (standard rate and concessional rate) for their GST regimes. The complex multi-rate GST structure puts pressure on Indian businesses to focus on nomenclature, branding and the technical nature of the goods and services it supplies, in order to get the right rate.

In the area of food and produce, the issue of classification is most stark. The Indian GST classification structure is based on a global system of nomenclature and classification called the Harmonised System of Nomenclature (HSN) developed by the World Customs Organisation (WCO). The HSN is a highly scientific system of classification and for most industrial products it provides clear and certain entry for classification. Even for food and produce items, the HSN provides a clear system of classification. However, Indian culinary products and innovations are not specifically covered and the Indian GST regime has added entries that are in addition and sometimes in variance to the HSN. It is here that confusion regarding classification arises.

At the same time, the changing culinary preferences of millennials have presented a huge business opportunity for innovation in the sector. Llifestyle changes in favour of packaged, canned/ frozen, ready-to-eat, ready to cook or pre-packaged food items have provided impetus for food entrepreneurs to set up shop in India. Changes can be seen across the farm to fork value chain. There has been a paradigm shift from the unorganised sector to branded food operators and chains in India. The introduction of new flavoring agents, proprietary food from fusion of cuisines, health supplements bridging the nutrition gap, and, innovations in food preservation and packing has posed a unique challenge in the taxation regime. With this background, we wanted to illustrate some of the current issues that the food and beverage business is facing to highlight the challenges classification poses for businesses as relates to GST. These are real issues and from our experience classification can have a huge impact on the survival of the business itself. In the food and beverage areas, the following are important examples:

- Applicability of GST exemption in relation to curd and yogurt. The scientific meaning of the product has a crucial role in determining the GST rate. The issue is compounded by healthy and vegan alternatives with flavoring agents.

- Applicability of Compensation Cess on carbonated fruit beverages. The importance of allied laws such as regulations issued by Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) and the trade parlance test in determining the correct classification. Carbonated fruit beverages qualifying as a ‘fruit juice based drink’ to attract concessional GST rate is highly litigated by the department.

- The meaning of ‘bread’ under HSN and its applicability to various Indian breads namely roti, chapatti, paratha, thepla, naan, kulcha, etc. Making this even more complicated are new categories of the bread-family of products such as: frozen, ready-to-eat, ready to cook packages are introduced.

- Branded products attract higher GST rates. The usage of proprietary marks, standardisation of packing materials, sale from branded retail chains, etc. pose unique challenges in applying the GST rate in the forward supply chain.

- The flavoring agent and its impact on classification of products. In trade parlance test, the influence these agents have on consumer behavior is critical to the classification and in availing concessional rates. Further, marketing and product positioning also impact the perception and ultimately the classification of a product.

Issues based on technical meaning of a product

Curd or yogurt and GST exemption

A wide variety of fermented milk-based products are available namely, curd, yogurt, artisanal curd. The products are marketed as fermented dairy product, lactose-free curd with added probiotics and flavoring agents. The health benefits of such products are highlighted. In general, the ingredients of these products include pasteurised toned milk, milk solids, enzymes, active probiotic cultures, active live cultures and minimal lactose.

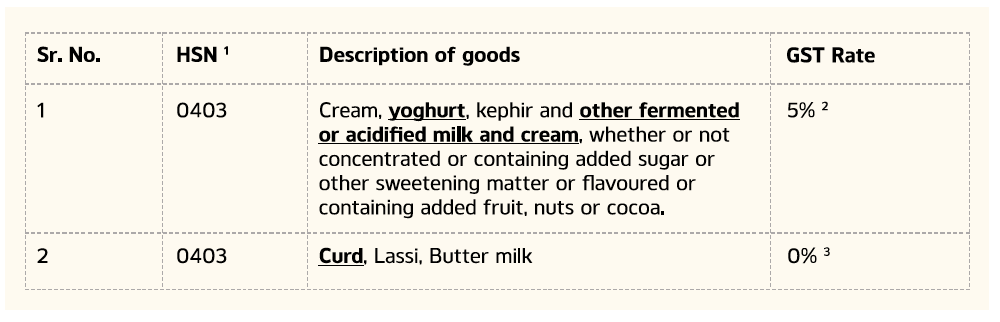

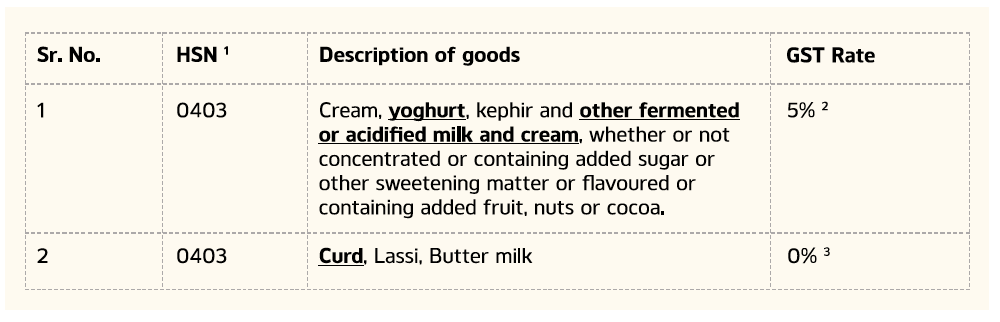

Curd and yoghurt are both types of fermented milk products but there are two different GST rates for classifying fermented dairy products and hence a confusion as to the applicable rates.

Merely looking at the table above, it is clear that whether a product is classifiable as ‘curd’ or as “yoghurt or other fermented or acidified milk and cream” can have significant GST implications. As with all classification matters, before considering the description, the classification under HSN needs to be determined (in terms of column 2 of the above table). The explanatory notes to the HSN clarifies that Chapter Heading No. 04.03 of Custom Tariff Act, 1975 (CTA) covers buttermilk and all fermented or acidified milk. The fermented dairy product manufactured from milk will be classified under Chapter Heading 04.03. Therefore, clearly both yogurt and curd fall under Chapter Heading 0403. The Indian GST notification, however, goes a step further and creates a sub classification for Curd with NIL rate of GST. It is hereafter that various rules and laws relating to classification come into play.

In India, the curd/dahi is a daily use product of the common man. Generally, consumers consume various kinds of ‘curd/ dahi’ and ‘yoghurt’ is also used as a substitute for curd. The classifications in such matters can be resolved through the robust route of technical differences between the product or by means of a simpler common parlance understanding of the products. The technical literature of ‘curd’ and ‘yoghurt’[ K. T. Achaya, A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food (Oxford University Press, 2001); David A. Bender, A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition, (Oxford University Press, 2009); British Food Manufacturing Industries Research Association et.al., Food Industries Manual, (Blackie Academic & Professional, 1988)).], distinguishes curd as made of starter probiotic cultures such as Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus lactis, etc. and yoghurt, will have other active live cultures such as S. thermophilus, L. bacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, L. bacillus delbrueckii subsp, lactis,L. occus lactis subsp. Lactis, L. coccus lactis subsp. Cremoris., etc. Accordingly, based on the technical specification, curd and yoghurt can be distinguished.

On the other hand, the marketing campaigns of ‘curd / dahi’ and ‘yoghurt’ and consumer preferences will have a role in determination of classification under the common parlance route. The packaging, the common man’s perception of the differences between curd and yogurt and materials accompanying the product all play a role in this process. Various courts have taken different approaches to classification of products, sometimes a common parlance method is preferred and in other times the technical meaning The issue of yogurt as curd is likely to go down the path of the courts where the answer to this question will be settled in the future. But until then, the suppliers will still need to grapple with the story of these fermented milk products.

To read the rest of the article, please click on the download article link provided below.

Click here to download the complete article

Click here to download the complete article

Size: 768 KB | 15 pages