In the case of Ferid Allani v. Union of India and Ors., the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (‘IPAB’) set aside the refusal order of the Indian Patent Office (‘IPO’) and allowed the appellant’s patent application.

After juggling the matter between the Delhi High Court, the IPO, and the IPAB, primarily over the issue of patent eligibility of computer-related inventions under Section 3(k) of the Patents Act, the claimed invention was acknowledged as patentable in view of the ‘technical effect’ and the ‘technical contribution’ of said invention. The silver line is that the courts and tribunal in India are aligned to the jurisprudence developed in the US and the EU in granting patents to computer program enabled inventions. However, like in any other jurisdiction, some examiners or controllers may exercise narrow view of granting patents for such subject matter. A huge credit goes to the applicant for his conviction in the merits of the invention and his faith in the Indian judicial system. After many battles, including twice in the IPO, twice in the IPAB, and twice in the Delhi HC, the applicant finally won the war and got a well-deserved relief. The decision also confirms the view that Indian IP jurisprudence is still developing and that interference by the Courts is not avoidable in all circumstances

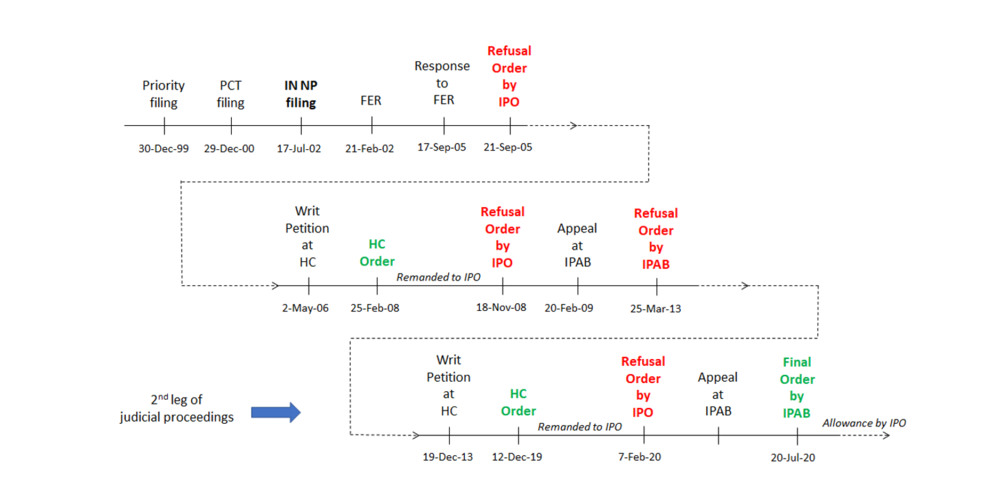

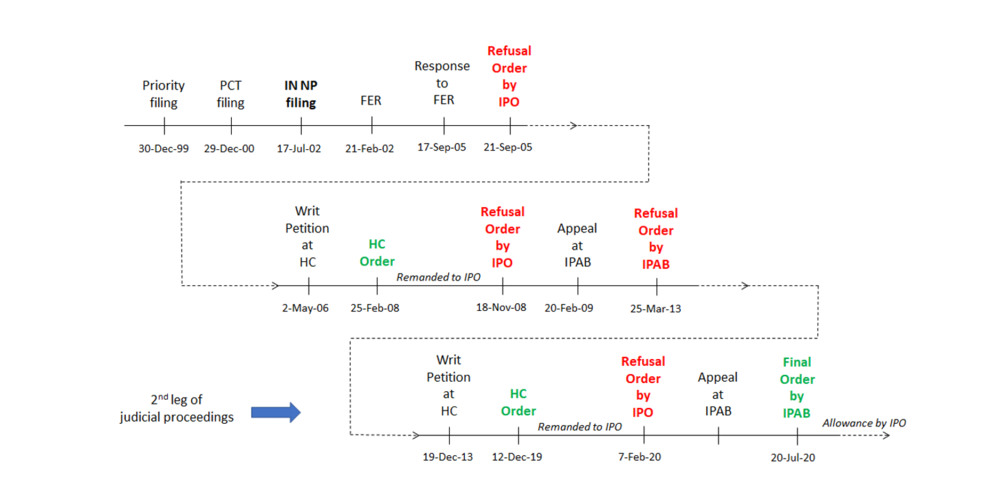

The write-up below provides the facts of the case, the timeline, a summary of the second leg of proceedings at the Delhi HC, the IPO and the IPAB, and conclusions.

Facts of the case

The appellant, Ferid Allani, a citizen of Tunisia, filed the national phase patent application no. IN/PCT/2002/00705/DEL with the IPO. The application was titled ‘Method and Device for Accessing Information Sources and Services on the Web’. The IPO, after examining the application, issued a First Examination Report (FER) objecting the method claims for being directed to computer program per se under Section 3(k) of the Patents Act, 1970 and the device claims for lacking novelty and inventive step over the prior arts cited in the FER. The appellant responded to the FER along with claim amendments.

The IPO examined the appellant’s response and the claim amendments and issued a refusal order stating the claimed invention was still not novel and inventive and was directed to computer program per se under Section 3(k). The IPO pronounced the refusal order within 4 days from the date of filing of the response to FER, without giving a due opportunity to the appellant, through an oral hearing, to address the outstanding objections.

Facts associated with the first leg of judicial proceedings:

The appellant filed a writ petition before the Delhi HC challenging the contentions raised in the IPO’s refusal order and asking for an opportunity of hearing in accordance with the principles of natural justice. The Delhi HC remanded the matter back to the IPO, directing the IPO to provide to the appellant an opportunity of hearing, in accordance with the provisions of the Patents Act before deciding the appellant’s patent application.

Subsequently, the IPO issued a hearing notice and upon hearing the appellant rejected the patent application concluding that method claims 1 to 8 were directed to computer program per se and were thus non-patentable under Section 3(k) and device claims 9 to 14 lacked novelty and inventive step.

The appellant then filed an appeal at the IPAB, against the IPO’s refusal order. However, the IPAB dismissed the appellant’s appeal and affirmed the decision of the IPO of refusing the patent application for lacking novelty and inventive step and for lacking ‘technical effect’ and ‘technical advancement’.

Facts associated with the second leg of judicial proceedings:

Aggrieved by the IPAB Order, the appellant filed a writ petition in Delhi HC. The Delhi HC disposed the petition and directed the IPO to re-examine the appellant’s patent application.

In response to the directions of the Delhi HC, the IPO scheduled a hearing and reviewed the oral submission made during the hearing and the written submissions filed post hearing and again refused the patent application on the ground that the claimed invention lacks novelty and that the invention as claimed in claims is a computer program per se, as provided under Section 3(k).

The appellant again challenged the IPO’s refusal order before the IPAB. Since the term of the patent was nearing its expiry (on 29 December 2020), the IPAB heard the appeal on urgent basis and pronounced the Order, directing the IPO to allow the appellant’s patent application.

The timeline of the case is illustrated below.

Delhi High Court proceedings and the order dated 12 December 2019

The appellant, in the writ, stated that the specification discloses a technical effect (for overcoming Section 3(k)) and a technical advancement (for establishing inventive step over the cited arts). The appellant relied on the examples of ‘technical effect’ recited in the Draft Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions, 2013 to assert that an invention which would allow the user more efficient data base search strategies, more economical use of memory or higher speed, etc., would constitute ‘technical effect’ and thus the rejection of the patent is not in accordance with law.

During the proceedings, the following was stated to reiterate the well settled legal position in respect of patent eligibility of computer-related inventions in India and abroad:

- The bar on patenting is in respect of ‘computer programs per se….’ and not all inventions based on computer programs.

- The words ‘per se’ were incorporated against the term ‘computer program’ in Section 3(k) so as to ensure that genuine inventions which are developed based on computer programs are not refused patents.

- The use of the word ‘per se’ in Section 3(k) suggests that the legal position in India is similar to that in the EU, as Article 52 of the European Patent Convention excludes computer program ‘as such’ from patentability.

- The ‘effect’ that computer programs produce, including in digital and electronic products, is crucial in determining the test of patentability.

- Patent applications for the computer-related inventions would have to be examined to see if they result in a ‘technical contribution’.

- If the invention demonstrates a ‘technical effect’ or a ‘technical contribution’, it is patentable even though it may be based on a computer program.

In light of the above, the HC remanded the matter back to the IPO and directed the IPO to re-examine the claims in accordance with the judicial precedents and settled practices of patent offices (across globe), including the Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions, 2017.

IPO proceedings and the refusal order dated 7 February 2020

The Controller, at the IPO, scheduled a hearing with the agent of the appellant for 27 January 2020. The Controller heard the agent of the appellant at length and pronounced a refusal order yet again on 7 February 2020.

In the refusal order, the Controller referred to plethora of the EU and the UK case law[1] and established that there is an inconsistency in the stands and tests for patentability of computer-related inventions across the UK and the EU (as indicated by Symbian). The Controller also quoted portions of HTC Europe Co Ltd v. Apple Inc. that states ‘technical effect’ and ‘technical contribution’ appear to be synonymous and the ‘technical contribution’ test is a singularly unhelpful test for determine patent eligibility because the interaction between hardware and software in a computer is inherently ‘technical’ in the ordinary sense of the word.

The Controller went on to state that while the four-step test laid down in Aerotel is still relevant, each case must be determined by reference to its own facts and features (as stated in Symbian).

In his assessment, in respect of the novelty and inventive step issues, the Controller stated that the objective of the claimed invention is the same as that of the closest prior art D1 (EP0847019A1) and the claimed subject matter has no technical difference with respect to D1.

With respect to the assessment for computer program per se under Section 3(k), the Controller was quite bold to state: (a) D1 has a technical advancement over the claimed invention; and (b) the claimed invention negates the disadvantages associated with the general concept of searching on the web. He recited the following excerpts from Aerotel:

This approach – sometimes called the ‘contribution approach’ though the word ‘contribution’ is not always used in this debate with precisely the same meaning - requires one to ask: what has been added to what is old? If all that has been added is an excluded category (in that case a computer program) then the claim is to the excluded matter as such. Inherent in the approach is an inquiry as to what actually is old.

In our opinion, therefore, the court must approach the categories without bias in favour of or against exclusion. All that is clear is that there was a positive intention and policy to exclude the categories concerned from being regarded as patentable inventions. We must simply try to make sense of them using the language of the Convention.

Based on the above excerpts, the Controller asserted that the technicality and structuring of queries for web-based search pertains the field of computer programming and therefore the question of technical contribution doesn’t arise, and no other approach could be taken for consideration in view of the legislative intent, behind European Patent Convention.

Reading the refusal order, it clearly appeared that the Controller had made up mind to refuse the patent application as he cherry picked the caselaws to provide his arguments. It is not at all surprising that once the decision to refuse a patent application is made earlier by a Controller at the IPO, the Controller will most likely provide reasons to substantiate his decision in case the application is remanded back to him by a high forum.

IPAB proceedings and the grant order dated 20 July 2020

The IPAB heard the counsel of the appellant and showed their surprise that the respondent did not counter or made an appearance during the proceedings before the IPAB.

The IPAB, in the order, stated that the Controller at the IPO erred in his assessment at multiple levels, namely:

- incorrect identification of D1 as relevant prior art, since D1 and the claimed invention have different objectives and provided different solutions.

- no appreciation of the technical effect (reduction in bandwidth usage and search mean-time duration) and the technical contribution (generation of more precise search query locally in the client device and delay the hit of the singe search query to the web) of the claimed invention.

- incorrect stand that the EU guidelines shall supersede over the Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions, 2013.

- not referring to the Indian Guidelines for Examination of Computer Related Inventions that provide cogent and coherent guidance in terms of the indicators of ‘technical effect’.

- incorrect reliance of the judgment in Aerotel to conclude it as the definitive statement on the law on patentability of Computer Related Inventions, in the United Kingdom, since Aerotel was not centered around the concept of the term ‘technical contribution’.

The IPAB went on to state that the Controller, though had cited Astron Clinica Ltd. v. Comptroller General, 2008, R.P.C. in the refusal order, but failed to rely on its guidance on the aspect of ‘technical contribution’ that in the case of a computer related invention which produces a substantive technical contribution, the application of step (ii) (of the four-step test of Aerotel) will identify that contribution and the application of step (iii) (of the four-step test of Aerotel) will lead to the answer that it does not fall wholly within the excluded matter.

In view of their finding, the IPAB concluded that the present invention had a significant technical contribution to the state of the art (i.e., the art before the priority date of the appellant’s patent application) and possessed a critical technical effect, and accordingly allowed the appellant’s patent application.

Conclusion

By setting aside the IPO’s refusal order, the IPAB quashed the notion of the IPO of not giving weightage to ‘technical effect’ and ‘technical contribution’ for the purpose of assessment of patentability of computer-related inventions. The IPAB promulgated that assessment of ‘technical effect’ produced by the invention is essential and just because a computer program is used for effectuating a part of the invention, it does not provide a bar to patentability. The IPAB also affirmed that the invention must be examined as whole and the ‘technical effect’ and the ‘technical contribution’ associated with the invention are the essential factors in deciding the patentability of computer-related inventions.

[The author is a Joint Director in IPR Team at Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan Attorneys, New Delhi]

- [1] Vicom (T0208/84) of European Patent Office, Boards of Appeal; AT&T Knowledge Ventures/Cvon Innovations v Comptroller General of Patents [2009]; IBM (T0006/83) of European Patent Office, Boards of Appeal; IBM (T0115/85) of European Patent Office, Boards of Appeal; Merrill Lynch's Application [1989] R.P.C. 561; In Re: Gale’s Application [1991] R.P.C. 305; Hitachi, Decision of Technical Board of Appeal 3.5.1, dated 21 April 2004; Fujitsu Limited's Application [1997] R.P.C. 608; Duns Licensing (T0154/04), Boards Of Appeal of The European Patent Office, 15 November 2006; Aerotel Ltd. v Telco Holdings Ltd & Ors, In the Supreme Court of Judicature, Date:27 October 2006; Symbian Ltd v. Comptroller-General Of Patents [2009] R.P.C.; HTC Europe Co. Ltd. v Apple Inc., Date: 3 May 2013; Astron Clinica Ltd. v Comptroller-General [2008] R.P.C.